Greater Water Parsnip

Sium latifolium

Max Parfitt

When waiting to hear which plant I had been assigned I was hoping for one of two things. Either something instinctively emotional, evocative of fragrance and beauty – honeysuckle, alpine lady, or lily of the valley – or a more exotic offering – the green winged orchid or devil’s-bit scabious (does anything roll off your tongue with more glee than the “devil’s-bit scabious”?). Both routes were sending my mind leaping down ten alleyways at once, finding the loves, the whims, the tragic misunderstandings and sorrows – even the maidenhair spleenwort seemed to have just enough “maiden” to make it a character in Hardy.

I open the digital raffle ticket.

Greater water parsnip.

It’s Valentine’s Day, you light the candles, you have roses lining the table and petals trailing to the door. You carefully select a bottle of wine… and a parsnip. The image doesn’t work. This plant may only be a vague relation to its edible cousin, but there’s still something deeply unromantic in the name (perhaps second only to turnip or kidney vetch) and it isn’t helped by the first word of its description, marked out in cold capitals: TOXIC.

That said, the more I read, the more I found…

On a purely factual level, the greater water parsnip is an umbellifer – a member of the parsley family with umbels (flower clusters that splay out on small stalks much like the seeds from the head of a dandelion). It has a tall, hollow stem (sometimes reaching up to 2 metres tall) and gives off a slight smell of paraffin (a subtle hint at its toxicity). But what struck me most was a sense of balance or even contradiction – not simply between its grand stature and particularly delicate flowers, but in its very nature.

The plant is a mother – to the darters, dragonflies, and damselflies mating in tight emerald and azure balls on her stem; to the curlews and snipe that shelter beneath her umbrella umbels; to the kingfishers and sand martins that burrow into her roots to make their nests. And yet she is toxic – loving and deadly; maternally welcoming and best handled through plastic gloves.

These contradictions are carried through into the plant’s preservation. The greater water parsnip is endangered due to the draining of its wetlands and has been protected since the 1980s, but environmental groups still struggle to support it. If you fence it off, it is overrun by nettles and brambles, and if it is left entirely in the open, it is either eaten (by those animals to whom it is not toxic) or trampled to nothing. Projects to look after the plant have been forced to search for a “Goldilocks” point – a perfect middle way between isolation and full exposure.

The greater water parsnip is no lady or lily, nor even devil, but she does somehow remind me of one of Dickens’ quirkier characters: the goldilocks mother making the best of a difficult circumstance – loving and violently protective, resilient and delicate, and living on a knife-edge.

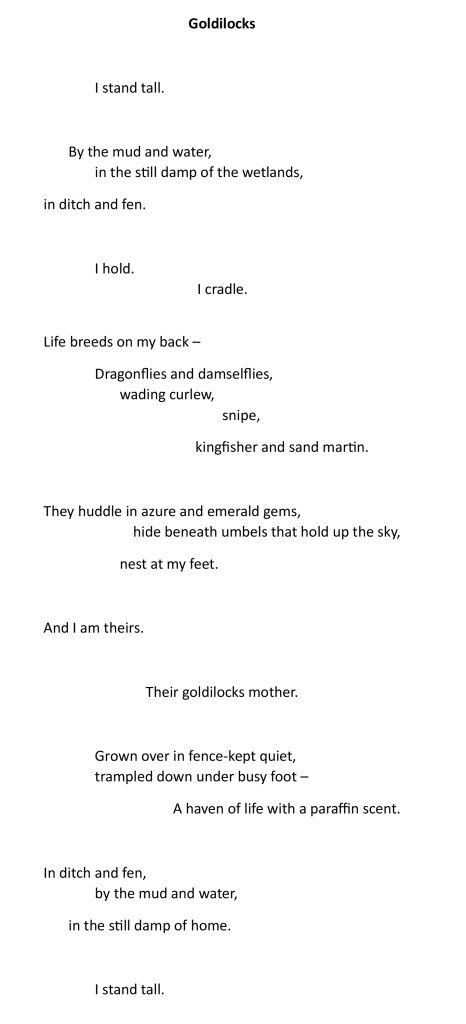

Image by Max Parfitt