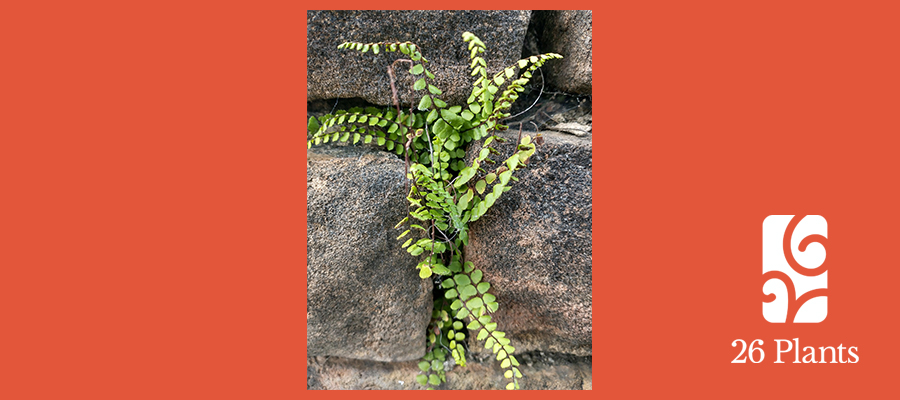

Maidenhair Spleenwort

Asplenium trichomanes

Kaye Brennan

Before we arrived,

this ferniest of ferns took hold on the cliffs

moved out,

to the walls Jack built.

She must have felt the need for decoration.

Maiden

Hair – not clinging, waving – choosing

to be there,

good for guts

bad for babies, so easy

on

the

eye

– where I least expected;

tough tufts of

emerald heart-shaped ribs,

shiny

scaly

spines.

Roots in grey brown brick rock altars.

Laying waste to order, greens on green

giving shade

as wort holds fast

to mortar.

Now I look at walls in a whole new way.

Smooth stones fixed, alive

before we arrived.

I love a fern. Such structured extravagance.

So imagine my delight to be asked to dig a little deeper into the story of the spleenwort, Asplenium trichomanes. More enchanting was to instantly learn a new word in wort, for plant. I find her etymological origins are in Latin, Greek and ancient English, and meet a fern family of 700 different species. Asplenium is truly an intriguing study. But what is her point?

Digging in, I learn her story begins pre-human (‘before we arrived’ as I read online) but she’s soon fated to offer a range of medicinal benefits not limited to the spleen; as a cure from dysentry to hair loss she’s even a fern-y friend to the 21st century homeworker, able to absorb radiation from our computers.

There are ancient meteorological links as well, invoking Hopi Indian elders crafting prayer sticks painted with water that this plant had soaked in, to bring forward the desperate, nurturing rains. Sciophilous, shade seeker, it’s out of the sunshine where you will find her happiest.

So named by our ancestors due to a perceived likeness to silken hair tresses, the connection to the maiden state comes from the myth that only a virgin could hold spleenwort fronds without the leaves waving.

And yet in further, contrasting, mythology the maidenhair fern is linked to female infertility. How the patriarchy subsumes us.

The way some plants make growing on a sheer rock face look entirely natural is surely impressive. This one such wort arrives, unbidden, to find just the right slot for enquiring roots to hold fast to. Coincidentally, four have recently made a home at the entrance to my wild garden, chosen (bidden, these) to frame the stone step discovered under the now demolished old shed they do so beautifully – reaching across the flat rock, emerald ladders of toothy leaves stretch out, just like their sisters spotted nearby holding fast atop smooth, Bath stone walls.

Here they soften the dullness but are tough as boots, not a bit delicate despite their unlikely choice of settlement. Springing out from ancient cliffs and today’s brick mortar, Asplenium wears a jaunty look and (I now see) is often joined by tufts of equally opportunistic flora like the stinky-but-vibrant Geranium robertianum and sweet yellow Erysimum. (Only now do I wonder if those four will propel tiny spores of their own, on to the stones of the raised bed that looms above them, adding unbidden to my own Asplenium family?)

But no pollen, no fruits – I had to ask: how does she serve? Of course! Seeking the darker side Asplenium brings something crucial, however understated, which both people and wildlife need more than ever.

The purpose, shade. The message, hope. To notice these pretty plants is to marvel at nature’s tenacity. And find North.

Image: Photograph by Kaye Brennan