Swamp Helmet Orchid

Corybas carsei

Jayne Workman, New Zealand

The story of one

Maybe one day, there’ll be

more than one meadow

of tiny swamp helmet orchids,

embroidering the wetland grass

of Whangamarino, taonga

of our last ten percent,

where botanists seek,

on hands and knees,

elusive lilac blooms,

rarest of the rare.

Mysteries lie within

one leaf, heart-shaped of course,

one stem, millimetres high,

one flower, once a year,

crimson-hued petals pouting,

to sigh out seeds as fine as dust,

coasting sunlit westerlies,

to alight on damp soil,

where one secret suitor waits,

exquisite chemistry and

sparkling networks beyond,

allowing new life to unfurl.

Then we’ll learn about oneness,

maybe one day.

Secrets of the swamp helmet orchid

If we can’t see it, does it exist? If we don’t understand, does it matter? Like the butterfly in the Amazon, the tiny swamp helmet orchid seems to hold secrets – about life, nature, our future, how we’re all connected.

So, how did I find her? The Department of Conservation’s list of ‘nationally critical’ plants offers plenty of choice. Through a maze of Latin names and ‘endangered’ qualifiers (an education in itself), I was drawn to rarity, smallness – and flowers. Meet Corybas Carsei, named after Harry Carse when ‘discovered’ in 1912. There’s a handful left in one location (a closely-kept secret), in one wetland (Whangamarino), in one region (Waikato), in one country (Aotearoa New Zealand) in the world. At just 10-30 millimetres tall too, hers is an extreme kind of invisibility.

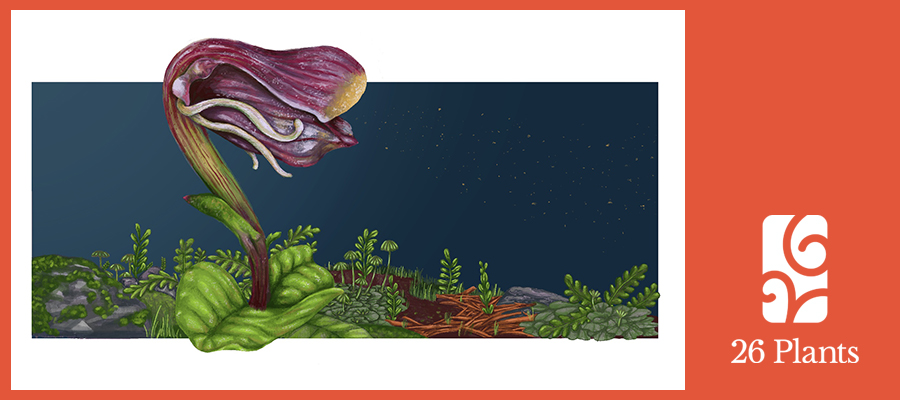

Her clunky, colonial names belie her unique provenance and refinement – intricate petals in delicate hues of crimson and lilac, a single heart-shaped leaf and stem elegantly bowed, each edge, frill and band of colour as perfectly reproduced as if she were full size. Mysterious too. Like the eels of the Sargasso or Atlantic, she’s kept us guessing about her reproductive chemistry. Unlocking its secret is the key to her survival – a difficult task made more so by one flower blooming once a year. Harder to find. Fewer opportunities for study.

Home is one of Aotearoa’s seven internationally important Ramsar sites and Te Ika-a-Māui’s second largest wetland. A seven-hectare complex of swamps, bogs and fens, Whangamarino, jewel of our remaining ten percent, is now finally respected as taonga, as Māori culture has for centuries. I imagine her cushioned among luxuriant liverwort, velveteen moss, cradled by a criss-cross of pūrekireki. Can I write, I wondered, without crouching, as Te Papa botanists do, carefully parting raupō to see a tiny crimson flower, damp soil beneath my knees?

I have to accept I probably never will. Most of us won’t. And that’s for the best. Orchid thieves and habitat erosion have encroached on her delicate ecosystem so much she was already considered extinct once. And, while the mystery of her dust-like seeds, that germinate with one unique mycorrhizal fungal partner in one small area, despite travelling its westerlies, is still only partly understood, there’s a risk she could disappear forever.

Does it matter? This tiny rare native orchid so few of us will ever see represents nature’s mystery, its more-than-human intelligence, its intricate networks and reciprocal communities, pulsing with vibrancy and life, a kind of liminal space in which nothing is known but everything connected. Who knows what part she plays? Maybe that’s our lesson.

Ramsar – The Convention on Wetlands adopted in the Iranian city of Ramsar in 1971

Te-Ika-a-Maui – Aotearoa New Zealand’s North Island

Whangamarino – 7,000-hectare wetland in the Waikato region

Taonga – treasure, anything prized, including objects, resources, ideas, techniques

Pūrekireki – tufts of sedge, common in swampy areas

Te Papa – Te Papa Tongarewa, New Zealand’s National Museum, Wellington

Raupō – bulrush, tall, summer-green swamp plant with a large flowering spike

Image by Georgia Pele