Mae Russell is a Ballads and Song Research Volunteer, taking part in the Strange Doings in London project run by Bloomsbury Festival and supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Ballads in Hand

By Mae Russell

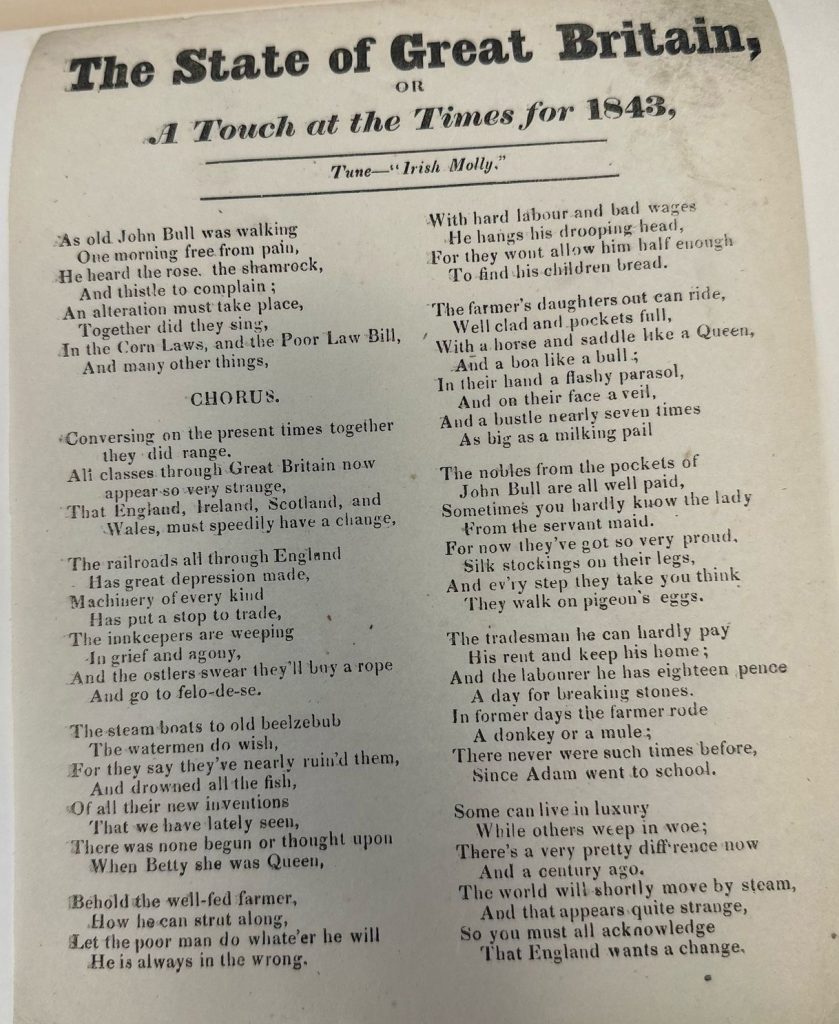

Our second research session for the Strange Doings in London heritage project brought us to the Rare Books Department at the University of Cambridge Library, where we explored the Madden Collection, an expansive archive of printed ballads. Unlike our guided and performative experience at the Charles Dickens Museum, this session was rooted in exploratory research. It gave us the chance to approach the material directly, without narration – just us, the pages, and the quiet of the reading room.

We were introduced to the collection by Dr Liam Sims, Rare Books Specialist, who welcomed us and offered a brief overview of the library’s holdings. He explained how these ballads, once considered too common or lowbrow to collect, are now recognised as rare and important sources of social history. Many survived by chance, rescued just before the print shops closed. Some pieces have only recently been catalogued, showing how active this work of recovery still is.

This made the experience feel especially meaningful. We weren’t just handling historical documents – we were engaging with materials that had nearly disappeared from the record altogether. Vivien Ellis, a ballad singer and researcher who is leading this heritage project, encouraged us to take full advantage of the opportunity to closely observe the pages themselves: their layout, texture, and typography. At the Charles Dickens Museum, we’d heard the ballads performed and discussed. Here, we were asked to study them first-hand.

The quiet atmosphere in the room reflected both concentration and a bit of awe. For many of us, it was our first time working directly with archival items of this kind. We carefully turned the delicate pages, comparing ballads, tracing themes, and sharing findings. One thing that stood out was how many ballads combined prose and verse – beginning with a brief written account of an event, followed by a lyrical retelling. It was a reminder of how intertwined storytelling and singing have always been.

The quiet atmosphere in the room reflected both concentration and a bit of awe. For many of us, it was our first time working directly with archival items of this kind. We carefully turned the delicate pages, comparing ballads, tracing themes, and sharing findings. One thing that stood out was how many ballads combined prose and verse – beginning with a brief written account of an event, followed by a lyrical retelling. It was a reminder of how intertwined storytelling and singing have always been.

The subjects ranged widely – from crime, political affairs, socioeconomic debrief, public hangings, and hardship to marriage, gossip, and satire. They captured snippets of London life from the perspective of ordinary people. Some ballads noted the tune to which they were meant to be sung, but most didn’t. As Dr Sims explained, all the ballads in the collection would have had melodies – but unless passed down orally, those tunes have largely been lost. And because these prints weren’t considered important enough to archive systematically, many remain unrecorded or uncatalogued even now.

What also struck me was how often the printer’s name and address appeared on the sheet: “Printed by J. Sharp, 30 Kent Street, “J. Catnach, 2-3 Monmouth Court, 7 Dials” or “C. Paul, 18 Great Saint Andrew Street, 7 Dials.” These details did more than authenticate the sheet – they grounded the ballads in real streets and neighbourhoods. These were London ballads, St Giles ballads. They were songs and stories from and for local people, rooted in place, and reflective of lived experience. The printers’ marks remind us that these weren’t abstract commentaries – they were shaped, printed, and shared by people just streets away from the scenes they described.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the ballads was the difficulty in distinguishing between fiction and non-fiction. Some were based on real events, others clearly embellished or invented, but many sat somewhere in between. This blurring of the line between fact and imagination reflects the nature of ballads themselves. They weren’t meant to be literal records, but emotional and cultural responses to everyday life. This tension feels central to the Strange Doings in London project. We’re not seeking neat truths, but uncovering fragments – emotional truths, social truths, expressive truths – that together form a fuller picture of St Giles’ past.

The final part of our visit took us into the library’s printing press room. Here we saw original presses, type blocks, and the physical tools that would have been used to create the ballads we had just been reading. It brought everything full circle. These weren’t elite or decorative texts. They were made quickly, distributed cheaply, and designed to be read aloud, sung, and remembered – or forgotten. Yet somehow, many survived.

The final part of our visit took us into the library’s printing press room. Here we saw original presses, type blocks, and the physical tools that would have been used to create the ballads we had just been reading. It brought everything full circle. These weren’t elite or decorative texts. They were made quickly, distributed cheaply, and designed to be read aloud, sung, and remembered – or forgotten. Yet somehow, many survived.

This session offered a different way of researching, one that placed the materials in our hands and trusted us to find meaning through looking, asking, and reading. It reminded me that heritage work is often as much about recovery as it is about preservation. And sometimes, the act of seeing a sheet of paper – torn at the edges, a printer’s name still visible, a forgotten tune once carried in its lines – can say more than any explanation ever could.

Read more about this project here.