Rob Andrews

Meenakshi Bhat: Meena sees

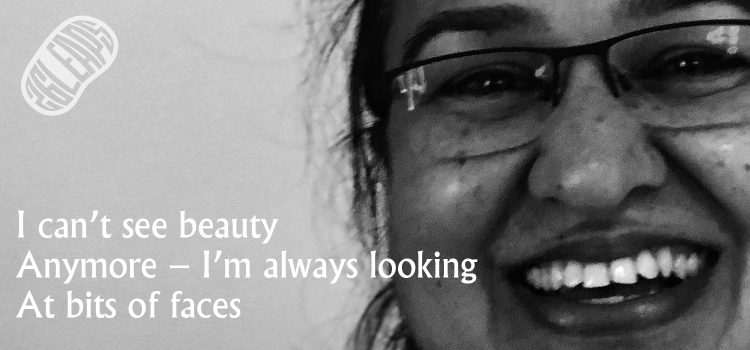

Meena says, “I can’t see beauty anymore – I’m always looking at bits of faces.”

But bits of faces offer their own beautiful revelations – the diagnosis of ten medical conditions from the shape of a septum, sixty from the line of an eyebrow. This is dysmorphology – the study of tell-tale signs written, almost imperceptibly, on our faces. Meena likens it to being able to see the 3-d image concealed in a stereogram – most people stare and stare and only ever see the surface clutter, some look straight through and clearly see the mystery hidden below.

Practitioners claim that everyone can be taught the rules, as her Great Ormond Street mentor Robin Winter taught her, but not everyone falls under its spell, leaving Bloomsbury every night on a high of discovery. Not everyone can see through the surface.

Meena is one of the gifted ones. In India – her birthplace, now home to her flourishing practice – perhaps the most gifted. She trains herself to be counter-intuitive; she hears hooves and thinks zebras. Where a thousand doctors would see malaria, she sees Gaucher’s Syndrome.

She is smiling and compassionate, but crushingly blunt. Children whose Gaucher’s is misdiagnosed long enough have one thing in common. “They’re dead.”

Ten years ago even diagnosis gave no remission. Meena could only counsel parents how their mis-matched genes would spark the same catastrophic enzyme malfunction over and over. Now Meena can talk about lives ahead.

But lifelong therapies need lifelong sustainability, and poverty kills hope. Solutions will have to come from unlikely places. Meena will know where to look.

Research story

Rob Andrews

Meena Bhat

Meena trained as a paediatrician in India. She was naturally inquisitive and fond of rare things – an odd enthusiasm that it took her a long time to discover had a name, dysmorphology.

A stint working for the NHS in London presented the opportunity to study with Robin Winter at Great Ormond Street Hospital. Her year at GOSH was, she says, “the best thing that happened to me”. Winter, a global giant in the field, passed on the savant’s eye for diagnosis, and Meena emerged with “the gift of looking at the world differently”.

It was a skill that she knew India needed more than anywhere, and she took the decision to leave family behind and return home. She rented a consultation room from a large hospital in Bangalore on daily wages and waited for the patients to arrive. For six months, no-one knocked on the door. Her peers were sceptical – why diagnose the untreatable? – but she marched the corridors of the hospital knocking on doors and persuading anyone who would listen.

Eventually the referrals came. Now her clinic – the Centre for Human Genetics – sees fifty new patients every week. Unlike most Indian hospitals, they do not charge for consultation – parents have worked hard enough to get their child referred.

Meena still has a passion for knocking on doors, but now those are the doors of government – looking for recognition for research into new affordable therapies and to secure funding that could start to change the lives of some of the 70,000,000 people she estimates suffer from rare illnesses in India.