Dr Rupert Whitaker is a psychologist, psychiatrist and founder of the Tuke Institute. In 1982 he co-founded the Terrence Higgins Trust, named after his partner Terry, one of the first people in the UK to die of AIDS.

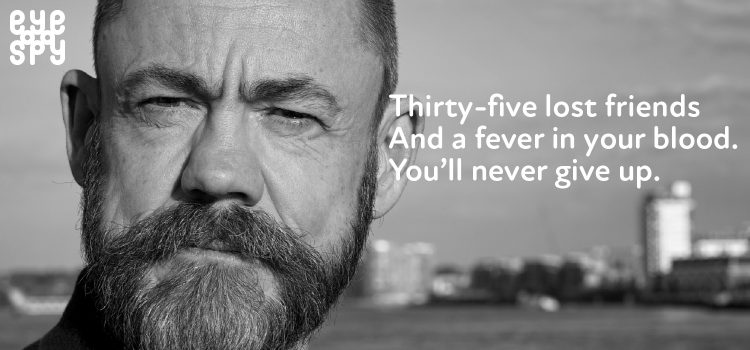

We talk over Zoom. You’re wearing a red T-shirt and glasses with translucent grey frames, your face half hidden by a fierce, dark beard, through which your smile breaks. You turn your screen round briefly to show me the high-up view from your window, over the green edge of Manchester.

Bloomsbury is far away and long ago. You moved there at fifteen to live with your dad in his flat near Russell Square, and within a year or two you’d found your way to the gay bars and clubs of the West End. Until then you’d known only classical music but now disco burst into your life as you took to the dancefloor with your friends, under the glittering lights. The scene was flowering and suddenly there were all these places to go, where it was safe to be yourself. It felt like things were just beginning.

Throughout those years you kept a diary, and in the back you wrote the names of everyone who died. The first was your boyfriend Terry, a former sailor, who’d freed himself from the Royal Navy by painting a hammer and sickle on the side of his ship. Terry was funny, sexy, and took care of you as no one had in your life before. But you had to listen to him dying behind the hospital curtain. Although you begged them, no one would tell you the name of his disease. It was so new it didn’t have a name yet.

You were nineteen, and already infected, losing weight and struggling to make it up the three flights of stairs to your dad’s flat. Your friends became your family, the only ones who understood what you were going through. One by one, they fell ill too, and they died fast. You watched as their families turned up at their bedsides and forced them to recant, repent, beg for God’s forgiveness. Rage possessed you.

The list in the back of your diary reached thirty-five names and then you stopped counting, because what was the point? The doctors gave you six months to live, but somehow you didn’t die. Instead you travelled, you studied hard; you became a psychiatrist, roaring your way through committee rooms and courtrooms, fighting for patients who couldn’t fight for themselves.

The virus that invaded your body remade you and remade your world. When I ask what your young self would make of you now, you cry but you laugh too, taking off your glasses to wipe your eyes. ‘I think I’ve become the person I would have wanted to be.’

These days you don’t often return to Bloomsbury. But when you do, you walk those streets and remember your friends.

Jill Hopper

Image: Rupert Whitaker, portrait by Andy Hewlett